Victorian flower arranging

Long before Gertrude Jekyll published Flower Decoration in the House in 1907 and Constance Spry opened her shop, Flower Decoration, in 1929, books on flower arranging had become popular with the Victorians. I’ve been looking through some of these old books, thanks to various internet archives, and realising just how influential nineteenth-century women were in introducing the idea of flower arranging as an art form. And as you’ll see throughout this post, I’ve been inspired by their suggestions to spend these last few rainy spring days making some little arrangements according to their instructions – with, I must confess, a dubious degree of success.

Bringing plants and flowers into the house has a long history, but in Britain the art of arranging only seems to have emerged in the Victorian age. As plant species from the colonies were brought back to Europe, they were transformed from objects of botanical interest into markers of wealth and status for middle-class and aristocratic homes. Books advising on cut-flower arranging began to appear in the mid-1800s. Some, like Thomas March’s Flower and Fruit Decoration (1862) and John Perkins’ Floral Decorations for the Table (1877), were directed primarily at male gardeners and florists, and advised on what to supply in terms of material for decorating the homes with flowers.

Others, written by women, focused more specifically on floral design, and the most important of these include the very first to appear, Miss E.A. Maling’s Flowers for Ornament and Decoration (1862) and Annie Hassard’s later and more comprehensive Floral Decorations for the Dwelling House (1875). As Maling observes, in 1862 the art of arranging flowers ‘gracefully and well’ was still ‘a very rare accomplishment’ and one in which women needed instruction, in order to do it ‘artistically’ so that everything looks ‘so simple and so natural’.

Dining à la Russe

The arrangement of cut flowers, Maling explains, had become an important matter, ‘both as a question of tasteful arrangement and skilful manipulation, and as a rather serious item of household expenditure; the dinner Russe requiring so very many flowers, and the taste for having them increasing with such rapidity’.

Service à la Russe became the fashionable style of dinner service from the 1850s onwards. Rather than all the dishes being placed on the table at the same time, and guests helping themselves (service à la Francaise, where the food inevitably went cold), the covered dishes were placed on a sideboard and servants portioned out the food one course at a time, according to the menu cards, and brought plates sequentially to each guest. Obviously, this required an awful lot of servants … but also an awful lot of flowers.

When all the food had been on the table, the elaborate serving platters and silver or gold plated dishes had functioned to display wealth, status, and taste. With service à la Russe, their place, and their symbolic function, was taken over by the table decorations, most particularly the flowers and greenery. And as the flowers became important, so did the vessels used for their display.

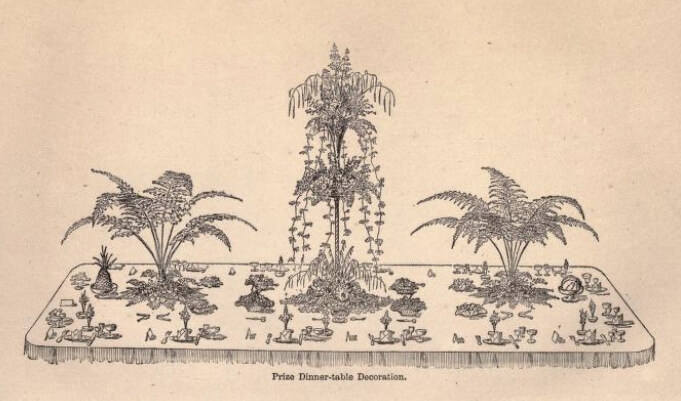

The most common centerpiece was the large and impressive March stand (invented by the aforementioned Thomas March). This consisted of a series of low dishes or tazzas set in tiers. On large tables these would be used in groups of three, with the tallest in the centre. The bottom of the stands would often be disguised with ferns, fruits and the like, and the dishes and trumpet filled with flowers: sometimes exotics recently introduced, and at other times, flowers more common to the English garden, like peonies and roses, and wildflowers, along with the much favoured grasses, wild oats and clematis, and various kinds of seedheads. Elaborate enough, one might think, but Annie Hassard recommends the March stand be supplemented by a trumpet vase rising out of the top tazza. One can only imagine the difficulties of conversing with one’s fellow guests around cascading plumes of grasses or the Eucharis amazonica.

Good taste

‘There is scarcely anything better enables a lady to display her taste than does the ornamentation of her dinner table’

‘Table Decorations‘, Girl’s Own Paper, 1887

Good taste is the phrase that recurs constantly, and there are pitfalls everywhere for the untaught and unwary. The choice of flowers cannot be made without considering the colour of the wallpaper or paneling, the effects of lighting – gas or candle light – and of course all the other items that must co-ordinate with the floral decorations on the table.

This gradually reached ridiculous extremes, particularly when Americans began to copy what they considered to be British standards. By 1907 Mrs Alfred Praga was providing literally hundreds of detailed possible ‘Schemes’ in her Dainty Dinner Tables, setting out not just the flowers and type of vase to be used for each scheme, but also – amongst numerous other things – the material and colour of the tablecloth and centre slip, the glasses, the menu cards, the candle sticks and their shades and even the specific sweets to be placed in the bonbon trays to match and complement the flowers. How to choose amongst so many possibilities … I know I would be reduced to a quivering jelly of indecision.

Into the drawing room

It wasn’t just the flowers for the dinner table that became markers of wealth, status, and taste. The drawing room was equally important. What might be considered too few flowers in the drawing room … or too many? Good taste lies in knowing the right point between the two extremes. While large vases were de rigueur on the dinner table, they were usually considered out of place in the drawing room, where visitors might end up vainly searching for a clear surface on which to perch their teacups and saucers.

Annie Hassard suggests that ‘gracefully grouped flowers in small vases, and a few specimen glasses placed here and there, are all that is required in drawing rooms’. Specimen glasses – the term frequently recurs in women’s advice on floral design – are what we now call bud vases. The term probably carried on from when flowers were studied as objects of botanical interest rather than used for decoration, but no longer refers to something as utilitarian as our idea of a specimen glass.

A great deal of attention is always paid to the shape and colour of vases. Constance Jacob, in her various articles on ‘Flower Decorations’ in The Girl’s Own Paper, is particularly emphatic about what is and isn’t tasteful. ‘Cheap so-called “opal” or “ruby” vases with crinkled or turned-over edges are unmitigated abominations’, she assures us, ‘and would vulgarise the most dainty blossoms’. Looking at a couple of examples, I’d tend to agree.

Tasteful vases

Many of the vases considered ‘tasteful’ – including Celadon, Etruscan ware, Japanese Imari – are probably no longer found in the average modern household. Coloured glass was iffy – ‘not very satisfactory unless one can afford Venetian’ – although Jacob grudgingly admits a few pleasing vases in peacock-blue or olive green can be found.

I have rather a fondness for green and blue glass and filled this one (no, not Venetian I’m afraid and with one of those abominable fluted tops, so C minus from Jacob I suspect) with what has become one of my favourite spring flowers: Epimedium. It has lovely leaves, and the outer petals of this variety are such a soft and subtle yellow, with a brighter interior that is exactly the same shade as the yellow wood anemones I added. I’d thought about putting some little flowers in this old china shoe that was part of my mother’s collection, but that plunged me too deep into the realm of twee.

Throughout the century, everyone agreed that blue and white vases and dishes were always in good taste. Even that later authority Gertrude Jekyll, who advised avoiding patterned vases altogether, declared the exception to the rule to be ‘jars of oriental blue and white porcelain, which are singularly becoming to many kinds of flowers’, including tulips, rose, peonies and lilies. Those colours are my absolute favourites, and I have many assorted china vessels in blue and white, so was quite chuffed to think Jekyll would consider this collection in good taste. Not many roses, peonies and so on out yet, so I settled for some other assorted spring flowers with a focus on blue anemones.

While there is nothing particularly Victorian about my displays, I was quite pleased with the result of limiting myself to blues and whites, both in vases and in flowers.

Small plain white china or specimen glasses in elegant shapes were also always considered in good taste. They are ‘invaluable when flowers are scarce’, Jacob says, ‘as a good sized blossom, such as a narcissus or dahlia, or a spray or a few delicate flowers is sufficient.’ Here’s one I was inspired to do for Easter. I wasn’t quite as restrained as Jacob would like, but thought it was quite pretty anyway. Or it was until the mini eggs disappeared.

Raiding the china closet

In advising suitable vessels for flowers, Jacob always, in interests of economy, keeps in mind the ‘probable contents of the average china closet’. In particular, she suggests using those ‘odd pieces of old china, glass and silver, which nearly every household possesses’, and especially those which have fond associations attached to them. I set about choosing a few items from my ‘china closet’, paying due attention to Jacob’s injunction that one should clean these vessels oneself, as association renders them ‘too precious to be trusted to the housemaid’s mercies’ (housemaid being otherwise occupied anyway).

While Jacob probably didn’t have egg cups in mind, I started small and simple with a little blue and white china egg cup that had been part of a set, along with a muffin dish, that belonged to my paternal grandmother. As the advice is to fill such vases with flowers having suitable symbolic meanings or associations, I thought to use forget-me-nots (as they are just starting to bloom here, I had to supplement them with sprays of blue brunnera).

Scent is ‘an important matter’ says Jacob, ‘in the room of a woman of refinement’, and for the drawing room she recommends violets with some small ivy leaves in tiny pieces of glass or china: ‘I always put such tiny bouquets on a small round table which supports a lamp.’ Our home is sadly lacking in table lamps, and the ivy running rampant once again in my garden has massive leaves, but I am overrun with violets and did find these tiny glasses, that my father had passed on to me. They must be ancient as they were in the china cabinet at his grandparents’ house in Hindley, and when he was a little boy he was allowed to drink lemonade out of them and he would pretend it was champagne.

These last two ‘arrangements’ don’t look particularly impressive or interesting to our modern eye, I’m well aware, but I include them because I think this underlines the primary difference between Victorian and contemporary books on floral design. As Maling said in 1862, the trouble with the untaught Englishwoman was that she would use flowers ‘either in form or colour quite unsuited to the things around them: arranging their vases, and decking their dinner-tables, with very little regard to the general harmony.’

‘Arranging’ is a term that seems to have different connotations for the Victorians and for us today. For the Victorians, flower arranging was all about choosing and using flowers with reference to the surroundings, to the room and the situation in which they were used, and that is partly why the vases are of such importance. Victorian floral decoration books provide information on which colours and which flowers harmonise, on the flowers that will last well in water, how to use sand and wire to support them, and so on, but ‘arranging’ is ultimately a matter of using flowers appropriately in specific contexts.

It’s often said that early twentieth-century designers like Constance Spry reacted against the ‘prim opulence and restrictive rules of Victorian-era flower arranging’ (Flower magazine), or broke with the ‘coercing of tightly massed blooms into stiff, globular forms’ (House and Garden). But like so many ideas about the Victorians, this seems to me an unsustainable generalisation based more on clichéd views of the Victorians than on actual evidence. From what I have read, there is little ‘restrictiveness’ in terms of how to put the flowers themselves together, certainly no interest in ‘stiff, globular forms’. There is no specific style to follow, no real instruction in designs like the crescent, the vertical, the triangular that came to be used in the twentieth century. And the only real ‘restrictive rule’ focuses on what today we have come to call a garden-centered approach: ‘All flowers’, as Jacob says and the others echo, ‘should be arranged with a due regard to their natural habits of growth … all other rules hang on this’. Perhaps it really isn’t such a jump from Constance Jacob to Constance Spry after all.

Receive updates via email of new articles.

Receive updates via email of new articles.

Latest Articles

Crazy about Cosmos

Flowers for summer bouquets I

Ranunculus Revisited

Review of Rachel Siegfried’s The Cut Flower Sourcebook

Tulips

Easter lilies

Spring has sprung: here comes the daffodil

Pleasures of the nose: fragrant flowers in early spring

Violets for Valentine

Reflexing flowers

Subscribe to My Blog

Enter your email address to receive an email notification whenever a new article is posted.

2 comments

Susan Hamilton

How interesting, Glennis. i rather like all these tiny ‘arrangements’ because they involve the simple pleasure of bringing flowers into the house rather than making ornate patterns out of them. I have no objection to the latter, but more readily imagine being able to simply bring flowers inside. I have yet to bring any of my own in, and might just start!

Glennis Byron

Oh me too! I’m definitely starting to add to my bud vase or little vase collection.